This is not really an essay about China. Mostly not, anyway. Over the last month, I’ve been back in the United States traveling. While this trip has taken me to New York, New Hampshire, and Georgia, I spent most of my time in my home state of Maine. There, I was struck by the parallels between the economic and demographic struggles of rural China and rural Maine. While both regions face challenges that are similar in many ways, they face these challenges with approaches reflective of their [different] respective political cultures.

I have mentioned before that my interest in China’s rural economic development is motivated by its connection to my own life. I want to see China’s experiments with rural rejuvenation succeed, not just for aesthetic enjoyment, and the benefit it has for the citizens affected, but for their practical case study value.

With that background in mine, I have decided to try writing about Maine. To help make it a little more insightful than just me and my personal observations, I also interviewed around ten people for this piece, including the current President of the Maine State Senate.

This is Part 1 of 2. In this first section, I will lay out Maine’s major challenges and introduce some programs and organizations trying to help.

Chapter 1: Keep Going North Until You Hit Canada

Maine is as far north and east as you can go in the USA without stumbling into Canada. We are a rural state, a sparsely-populated one, and one of the poorer states in the country (44th smallest economy and 40th lowest GDP/capita. We are generally known for lobsters and Acadia National Park and Stephen King novels and that’s it.

I come from the even more sparsely-populated northern part of the state, in Aroostook County. There are currently only 67,000 people in Aroostook, so don’t be too surprised if you’ve never met one of us out in the wild. In Aroostook, we drive pick-up trucks with hunting rifles in the gun rack, listen to country music, and inject a remarkable number of Québécois French phrases into our heavily-accented English (a patois which I lost as soon as I went to college, but inevitably pops out when I return).

Maine has the lowest violent crime rate in the nation and one of the lowest rates of property crime. We never lock our homes or our cars. Hell, we usually leave our cars running with keys in the ignition in the parking lot in the winter so the heat stays on. Jeezum rice, it’s cold up here! Who could steal a car anyway? Everyone already knows what everyone drives. You’d never get away with it.

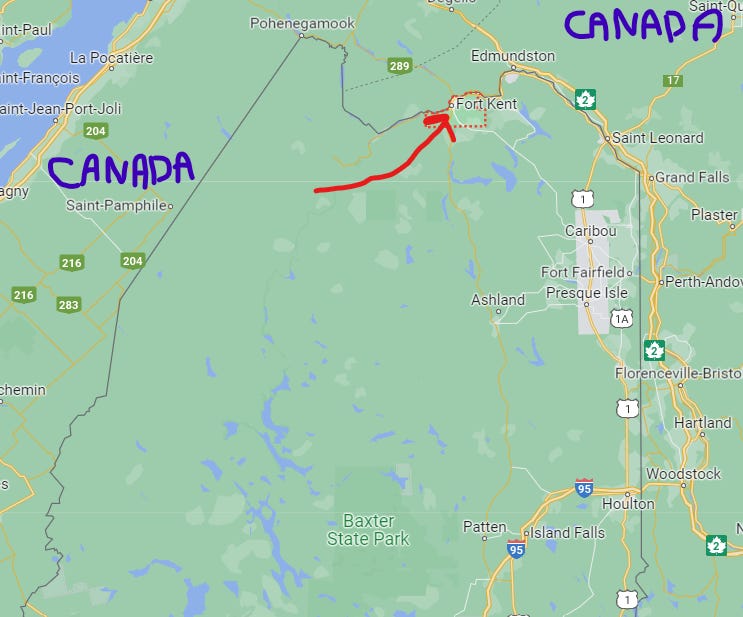

My hometown is Fort Kent, population: 3800. This is the northern endpoint of US Route 1 (the southern terminus is in Key West, Florida).

We have an international border crossing into New Brunswick, Canada. You’re equally likely to hear French or English spoken on the street. Your friends from southern Maine have heard of Fort Kent, but they have never been. They’ve always wanted to visit, but it’s just so far.

In the 80s, Fort Kent had multiple bars, restaurants, and a downtown that might be described as lively - rowdy even, on the weekends. Then, the local forestry industry dried up. Now, it’s a town that’s been treading water and barely keeping its head dry for three decades. Very little changes. The population slowly trickles down. New restaurants open, then close again. This year, just 62 students graduated from the high school.

We don’t have much of an economy to speak of up here. Historically, it was dominated by the production of forestry products and small-scale agriculture, with a bit of light manufacturing. While harvesting of wood and production of paper/forestry products is an important industry in Aroostook County, and a provider of well-paid blue-collar jobs, it is now struggling, due to cheaper international competition, reduction of paper use in a digitized world, and lack of workers.

In 1970, the paper industry employed a quarter of Maine’s total workforce. Today, production of paper products, wood products, and timber harvesting together employ fewer than 15,000 people statewide. The single largest employment sector in Aroostook is healthcare and health services, which is bound to keep growing as our population ages. The poverty rate in Aroostook is around 15% and likely closer to 20% or higher in Fort Kent. I don’t know if I’d go so far as to say the town is sick, but I wouldn’t say it’s healthy either.

As for the other industries from history, small-scale farming is rapidly disappearing too, while the light manufacturing is all but gone (mirroring its general decline in the US). Tourism has arisen as a new third-place contributor to GDP (behind wood harvesting/processing and agriculture) but still faces many challenges. I’ll talk more about tourism in Part 2 later. But for now, just know that our economy is…not great.

Chapter 2: Where Have All the Workers Gone?

Most of the country has a labor shortage right now. But for Maine, shortage is an insufficiently urgent word…it’s already a full-blown crisis, especially up in Aroostook.

Near my home is a gas station/convenience store owned by one of my teachers from elementary school. He told me after 15 years of running the place, he and his wife are going to put the place up for sale at the end of this year. This is not because business is bad, but because they’re exhausted. Even with the minimum wage set at $15/hour in Maine, they can’t find someone to work the cash register. They’re simply burnt out from working at the store 7 days a week, during what are supposed to be their retirement years. I hope the next owners are up for the task…(if they can find a buyer).

Aroostook’s population has been declining steadily for decades. Just like in China, young people of working age have few reasons to stick around the countryside, and increasingly choose to leave the area. While it’s not as extreme as what you’ll see in some Chinese towns, (which sometimes have literally nothing but elderly people and small children) we certainly seem to be trending in that direction.

While the factors contributing to Maine’s sluggish economic performance are of course more complex than just labor shortages, the lack of workers is certainly one thing that everyone can agree on as being a huge problem Entry-level workers, skilled workers, professional workers, it’s all the same. There are not enough people to fill jobs in Maine. The “Help Wanted” signs in storefronts across the state in everywhere from fast food to vehicle service centers are as ubiquitous as flannel shirts and orange hunting caps.

A look at the growth trend of Maine’s labor force for the past few decades tells the story clearly:

The shrinkage in the labor force has been especially pronounced in rural areas like Aroostook. That’s not shocking, considering the population overall has been shrinking for decades. Our communities are just withering away.

Not only is our population shrinking, but it’s also getting older. Families are having fewer children as cultural norms change and the cost of raising children keeps rising (Maine is full of Catholics allergic to contraception…those families used to be BIG).

Meanwhile, many young people are being siphoned away to more attractive careers downstate, or out of state. I think anyone who has spent time traveling in the Chinese countryside will see the similarities here.

In the Making Maine Work 2022 white paper published by the Maine State Chamber of Commerce, 500 Maine employers were surveyed on their priorities for the next Maine governor and the greatest percentage - 46% - selected “availability of entry-level workers” as their TOP concern, tied with energy costs. And that’s in the middle of an actual energy crisis.

But it gets even worse. Not just entry-level workers, but “availability of skilled/technical workers” and “availability of professional workers” were ALSO among the top priorities, both affecting more than 40% of the businesses surveyed. This tells me there simply aren’t enough people to work at any level in Maine.

Besides contributing to business closures, this has a dire impact on Aroostook’s ability to attract employers. Even if companies with well-paid, year-round jobs want to set up shop here, they’re going to struggle to find people to hire. These companies would have be extremely patient, or have some very strong motivation to come here in the first place.

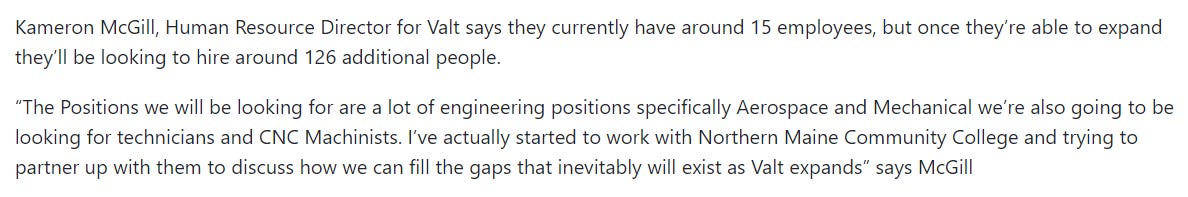

Recently, such a potential employer arrived in the region, Valt Enterprizes, a high-tech space and defense company that wants to use the small airport in the nearby city of Presque Isle to develop launch systems for satellites. I imagine Aroostook’s low population density is a big point of attraction; falling debris from any failed launches are unlikely to land on anyone or anything of value.

Valt is the first tenant of what is planned to become the Presque Isle Aerospace Research Park. Valt is looking to eventually hire over 130 people, including engineers, research scientists, machinists, etc. If this actually happens, it would likely become a major employer (and taxpayer) in the region. It’s exciting for local economic planners to see Aroostook directly benefitting from Maine’s intended new space and aerospace industry.

But opportunities like this highlight a chicken and egg paradox that arises when trying to attract such an employer. Even if there are enough workers in the region to fill these jobs, they will require specific training and degrees to fill these positions. Students will only choose certain educational tracks when job prospects after graduation look promising, but employers will struggle to see this region as attractive to locate their business if they believe they can find enough talents to hire. In this case, the local branch of the University of Maine in Presque Isle doesn’t have a 4-year engineering program, nor does the local community college have a 2-year machining program. Where will these talents come from?

To try to get around this, Valt has been forced to work with directly with local schools to provide job training just to fill their CNC machining positions:

Meanwhile, I imagine the positions that need engineering degrees will require employees to be hired in from outside the county, or even outside the state, to be relocated to Presque Isle. Not every employer will be willing to go through such a process. Finding one that will is crucial to breaking out of this chicken/egg paradox, which is why economic planners up here are so excited about Valt. But based on what I’ve been hearing from everyone, I’m afraid they’re going to struggle to find the people they need.

All of this is strongly reminiscent of rural regions in China, where the situation is probably even more dire. For instance, China has a great deal of trouble even securing teachers to work in rural areas, a serious and ongoing problem with no immediate structural fix in sight. I fear Maine will also be in such a state very soon.

Chapter 3: Who’s In Charge of Fixing This Stuff?

On this trip, I found a new business in Fort Kent that seemed to be doing well, a coffee shop called the Red Devil Roast. Not filter-drip, but a guy roasting his own beans and making barista espresso drinks, in a part of the world where most people have been happy drinking sludgy drip coffee their whole lives.

He told me he had previously traveled the world while in the military and sampled high-quality coffee, and eventually decided that what his hometown really needed was proper lattes…so he made it happen. Before opening his shop, he had to spend time learning to roast and prepare the beans. To cover those startup costs, he had applied for (and received) a small business loan from the Northern Maine Development Commission (NMDC).

I had never heard of NMDC before, but I took a look at their website and realized that if anyone would have opinions and thoughts about the strategic economic planning of Aroostook County, it would be these guys. NDMC is headquartered in the city of Caribou, Maine, not far from Fort Kent. So, I gave them a call and set up an interview/chat session with their Director of Economic Development, Jon Gulliver.

Jon told me NMDC is a nonprofit designated by the federal government to provide economic development services to rural communities in Northern Maine. They help towns with economic consulting, marketing, tourism development, attracting employers, etc. Since the 70s, they have also had a lending and community grant finance program, which is what the Red Devil Roast had taken advantage of.

He told me that when it comes to economic and strategic planning for small communities in the area, NMDC covers and provides support for much of the county. While some of the larger towns and cities have their own dedicated person to do strategic planning for the town, most will piggyback on NMDC’s services. NMDC is probably the closest thing Aroostook has to an organization whose job it is to “save” our communities.

I discovered NMDC is a membership organization - regional communities pay annual dues in order to use its services. Jon told me the dues only cover a very small portion of their annual budget though - most of it arrives via federal grants. As it shuttles these resources to local business owners and would-be entrepreneurs, NMDC’s public-private partnership identity becomes more clear to me.

One of NMDC’s long-term strategic goals for itself is to become self-sufficient and not so reliant on federal grants for funding. This is something their community financing and loans division has already achieved. This division provides bridge financing for businesses like the Red Devil Roast that are too early-stage or too uncertain for commercial banks to be willing to provide loans.

For me, this is reminiscent of China’s Rural Credit Cooperatives, established by the People’s Bank of China to offer micro-finance services in rural areas. But, the rest of NMDC’s role doesn’t seem to have a really clear corollary to any institutions I’ve encountered before in China.

I told Jon about my experiences traveling around the Chinese countryside, along with some of the initiatives put into place as part of the New Countryside program, including infrastructure development and creation of tourism/commercial enterprises that will hopefully entice young people to come to live and work in these communities.

“Yes, that’s the ‘if you build it, they will come’ approach” Jon said. “At the beginning, we also wanted to have a plan to grow our communities with people from outside. But now we’re just focused on trying to keep who we still have here”.

Jon told me that that during the early stages of the pandemic, Aroostook’s population actually grew for the first time in years, as people in cities bolted for the countryside. The gain was short-lived, however, and the long-term trend of population decline resumed again last year. The Making Maine Work white paper also pointed out that many of these new migrants still work remotely for out-of-state employers, which does little to alleviate the labor crisis.

Obviously Jon knows more about the details of Aroostook’s economic development than I do, but I can’t help but feel that setting an objective to “not lose people” is a bit of a low bar. In that scenario, even if you succeed, you’re just treading water, not making any forward progress. I feel it should be possible to attract new people into the region while simultaneously creating reasons for locals to stay here, instead of either/or. But possibly (even probably) I am just being naïve about a bunch of complexities I’ve not considered. At least an organization like NMDC exists. At least someone is trying to do something, although the approach taken is very different from what I’ve seen in China. Do organizations like this exist on a county level everywhere in the country?

That’s it for Part 1. In Part 2 in a few days, I’ll dig deeper into tourism, local politics, and try to identify some conclusions and insights for my patient audience. If you find this kind of stuff interesting, consider subscribing. Thanks for reading!

Some rural areas in the US are booming--see, for instance, many small towns in the Rockies and Sierras--or even Milbridge, ME down here in Washington County. What makes them boom? The Sonoran Institute (now Headwaters Economics) did a study more than 20 years ago and arrived at 5 factors that enabled communities that were once resource dependent (logging, ranching, mining, fishing, etc) to thrive once the resources could no longer support the community. I have a copy of the study if you are interested. Contact me at rsl@russellheath.net. Russell Heath

Very interesting David! Of course, the situation is very similar in rural Québec, or New Brunswick for that matter. Small towns and villages barely survive, and not every place can be a tourist attraction. So, pretty much the same as in China. On the other hand, in China they are still very busy building infrastructure such as highways and railways that help bring more tourists, and other businesses as well. First time I went to the Garze county in west Sichuan, it was almost three days of driving from Chengdu to get there. Then they finished the highway from Ya'an to Kangding, and if you leave in the morning from Chengdu, you are there before dinner. I also recently visited the Ruoergai area, north west of Sichuan, a (beautiful) high altitude plateau between Jiuzhaigou and Chengdu. I saw that they are building a railway, so there should be a high speed train within a couple of years. Not a chance, of course, that there would be a high speed train taking tourists from Boston or New York to the north of Maine! Also, it would still be difficult to attract enough tourists to make even a small town thrive, whereas China has a 1.4B basin of potential tourists. But right now, however, the internal tourism industry in China is in the doldrums. Even a normally hyper-busy place like Jiuzhaigou is "relatively" quiet (which just makes it pleasant enough to visit....). There were also plenty of tourists along the Ruoergai plateau, and locals offering horse riding all along the road. Yet for them, it is just supplementary income. Most families have a horde of yaks, 100 or more, that gives them enough of a basic income. I met a family where the husband went to work in the small town nearby, while the mother and grandmother took care of the yaks (I have some beautiful pictures). It is interesting that the government does not allow other types of agriculture to use that land, since that would destroy the unique and fragile ecology of the place, and the traditional way of life. I visited the yak research center, and it was quite a bit off the central road and not in the flat area but by the mountain side, for the reason that the government would not take good land from anyone. There, they were busy trying to breed better varieties of yaks, like mixing traditional yaks and angus beef. So all in all, the area, although remote, is quite dynamic. They are definitely not just sitting on their ass and hoping things will improve.