Life is a Highway: The Long and Winding Road to Poverty Alleviation

Are highways the unsung heroes of China's poverty alleviation campaign? Is it too much to use two road-related song metaphors in one title? These, and other topics, addressed within.

Let’s talk about Chinese highways for a minute, because they’re pretty cool and don’t get as much appreciation as they deserve. Now I admit, I’ve been guilty of failing to deliver that appreciation too. High-speed rail construction is impressive and sexy, and soaks up most of the coverage. But after using the Chinese highway system as a driver for the first time during my recent travels, discovering it to be excellent, and then doing a bunch of nerdy research, I've gained a newfound respect for the role that roadbuilding is playing (and will continue to play) in executing poverty alleviation and and enabling domestic consumption. That’s what inspired this piece.

I would have included links to my Twitter threads on my travels in Yunnan and Sichuan, but Twitter won’t allow Substack to embed tweets anymore. I’m @pretentiouswhat.

If you want to get rich, first build roads

There’s a whole medley of political, demographic, and luck-based factors that could contribute to a Chinese county or city falling behind economically, and finding itself impoverished, and not all of them will be present in every case. But there’s at least one thing that you can almost certainly count on encountering in all the least-developed, poorest places in China: crappy roads.

There's a folksy proverb in Chinese:

想要富,先修路 xiang3 yao4 fu4, xian1 xiu1 lu4

"If you want to get rich, first build roads”

(sounds better in Chinese, because it rhymes)

When looking for an explanation of why a region is poor, my first instinct is to look at factors like…weak natural resources, corruption, incompetent governance, or perhaps declining industry due to economic shifts (e.g. the US Rust Belt, or China’s northeast). However, when I mentioned to my wife I was researching the poorest counties in China, her first reply was: “oh, they must have poor transportation”. Then she mentioned that phrase I just shared above. Hmm. Another bit of Chinese common-sense wisdom that I was late to the party on. But it makes sense.

Now of course, crappy roads aren’t created on purpose; they’re generally forced to be that way by extreme topography, usually mountains. While these days they’re never completely disconnected from the greater road grid, China’s most remote counties often have nothing better than a single winding two-lane (or smaller) road connecting to the outside world, torturously traversing mountains and valleys via switchbacks and hairpin turns, ever-vulnerable to mudslides and avalanches, requiring a half day’s travel (or longer) of white-knuckle driving to the nearest economic hub.

With this in mind, it’s not particularly surprising that rural road improvement is one of the key pillars of China’s poverty alleviation and rural rejuvenation campaigns, both local-level roads and cross-region highways. After spending the last two decades building highways between the the large cities and provincial capitals, connecting remote, poor areas has already become the next area of focus for China’s highway planners. While High Speed Rail is certainly playing a major role in connecting major cities and creating economic activity in the East and South, shepherding along the path to a moderately prosperous society, I suspect highway construction is contributing much more than high-speed rail in terms of grassroots poverty alleviation.

I suspect highway construction is contributing much more than high-speed rail in terms of grassroots poverty alleviation.

To my mind, the key poverty-alleviation outcomes of highway building are:

Facilitation of urban-to-rural tourism in the hinterlands and border regions (that sweet, sweet domestic consumption)

Easier access to urban job opportunities for rural residents

Enabled sales of agricultural products in more-developed areas, where they may earn a higher price

Now, I’m aware of studies that show highways connecting more-developed and rural areas tend to benefit the economy of the developed area much more than that of the rural one. The regional economic hub can offer manufacturing and services more efficiently, and jobs that pay better, so it siphons industry and human talent away from the rural areas, forcing the rural areas to become even more specialized in agriculture. This might maximize efficiency in a classical economics sense, but could impede the goal of alleviating poverty in the rural area (although agricultural specialization of course doesn’t necessarily mean poverty-trapped, especially with government support programs and newfangled tricks like farm product livestreaming).

So, returning to the original point, if we’re looking for a narrative to support how highway-building can realize a poverty-alleviation effect in a rural area, I think it’s #1 - the tourism - that offers the most long-term sustainability and growth opportunities within the impoverished region. Cultivating a tourism industry creates jobs that arrest population drain and allow more wealth accrual than sustenance agriculture ever could, under less strenuous working conditions, all while stimulating domestic consumption. Doesn’t matter if the attractions are natural, man-made, or cultural, as long as city folk like me are willing to come spend some yuan. Having a highway is a big part of that.

A tourism industry creates jobs that halt population drain and allow more wealth accrual than sustenance agriculture, while simulating domestic consumption.

Let's look to some of my own anecdotes. On my last trip, with my brand-new Chinese driver’s license in hand, I found myself for the first time looking at trip planning from the same perspective as a car-owning Chinese consumer. Planning our trip between points on a map that could be reached within 2-3 hours of driving allowed me to spread my tourist dollars far more widely than I ever would have before.

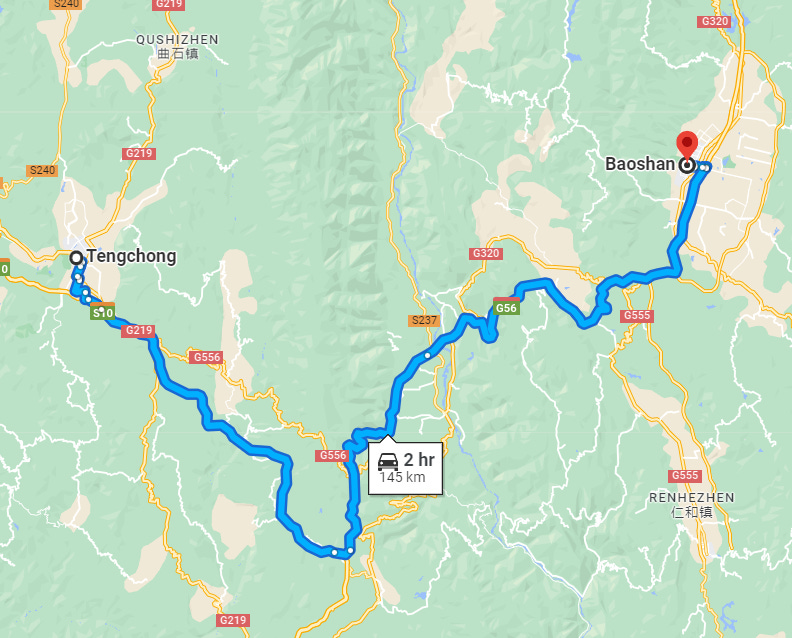

At one point on this trip, we drove from Baoshan to Tengchong, a tourist city of 600,000 people in western Yunnan, via the Baoteng Expressway, completed in 2016, a speedy and smooth 2-hour jaunt through the Gaoligong Mountains.

Tengchong itself was a fun little city on the Myanmar border with interesting hot springs, a volcano park, an ancient town, some snow-covered peaks, and some of the best food we found in Yunnan. It was a highlight of the trip for me.

Prior to the construction of the Baoteng Expressway, the journey from Baoshan to Tengchong would have taken 4+ hours via the old winding G556 highway, built in the 90s (also visible on the map above). Would I still have visited Tengchong without the Baoteng Expressway? Probably not…Eight hours of driving (roundtrip) is a huge commitment when you only have a few limited days for your holiday.

Would I still have visited Tengchong without the Baoteng Expressway? Probably not.

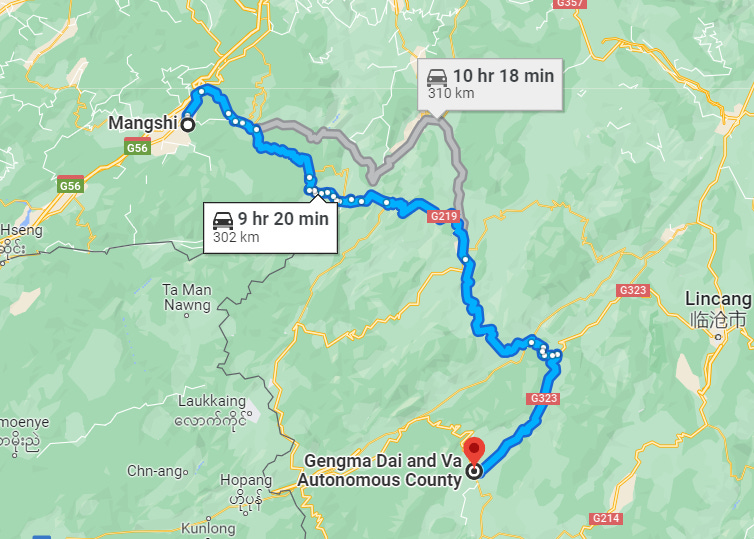

Backing up that idea, I can concretely point to an example a place that I didn’t visit, precisely because it was too hard to get to, and would use up too much of my limited holiday time. That place was Gengma County, in south-central Yunnan. On the map, it looked like it was basically adjacent to Mangshi, where our trip started. I punched in driving directions, and discovered that although it was just 300km (186 miles), it was going to be a 9 hour drive through winding mountain roads to reach Gengma from Mangshi. Thanks, but no thanks.

When the under-construction highways connecting these two areas are finished (around 2026ish), I’m sure my considerations will change.

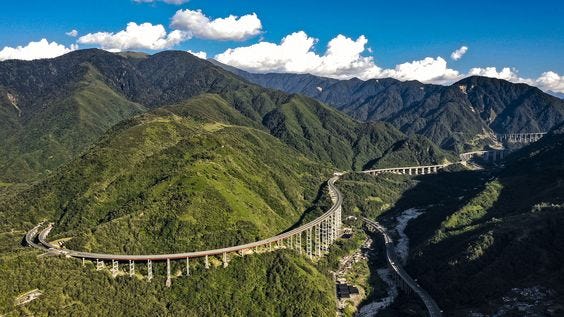

It must be emphasized that when it comes to these rural mountainous expressways, they are all horrendously expensive, remote, and technically difficult to build. China built the “easy” highways first, and what’s left now is pretty much all super expensive and challenging to execute. In the mountain areas, nearly the whole highway route will be flyover bridges or tunnels that sometimes stretch for dozens of kilometers.

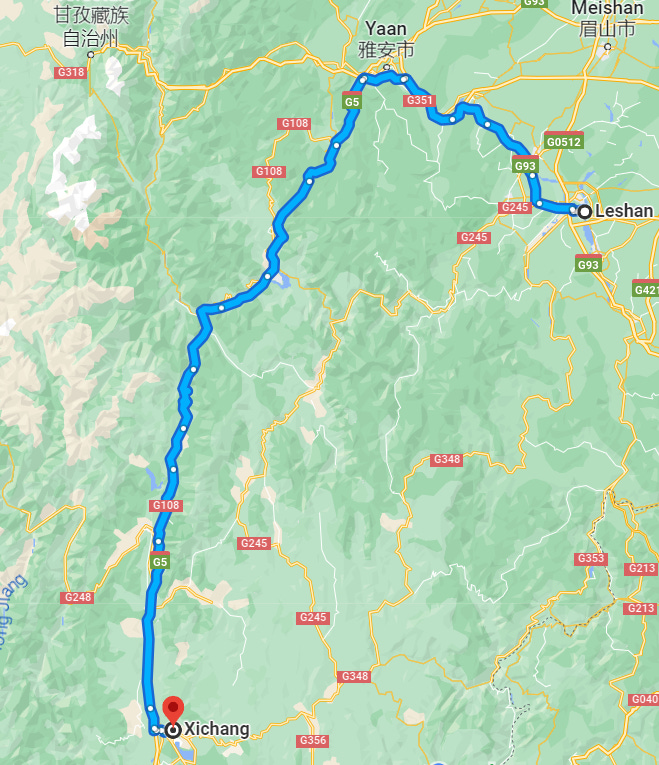

As an example, take the the Yaxi Highway in Sichuan, running between Ya'an and Xichang, which was completed in 2012 and cost a staggering 100 million CNY/km, for a cool 21 billion CNY total. (that’s ~22.5M USD/mile or ~2.98B USD total).

Obviously, this highway will never pay for itself via road tolls collected on traffic. From a direct return-on-investment perspective, it’s tough to justify spending 21 billion CNY to connect two small cities in central Sichuan.

- Ya'an, (雅安) a 4th-tier city with a population of 1.5 million.

- Xichang, (西昌) a 5th-tier city that, despite serving as the capital of Liangshan Autonomous Prefecture, has a population of just 900,000.

Even if the long-term value of increased economic activities along the route is estimated and included, covering 21 billion CNY seems a monumental task.

Now look, I’m not oblivious to the fact that government infrastructure spending like this grants a comfy boost to provincial GDP, and that this constitutes part of its attractiveness. Chinese provinces have been squeezing that lemon for a long time and keep finding juice, much to the undying chagrin of certain types of classical economists. I’m not gonna pretend this isn’t part of the motivation for building highway infrastructure in periods of economic volatility. Obviously.

But to be frank, it’s really too cynical to frame these infrastructure investments purely in terms of profit and loss, or as short-term GDP boost cheat codes. Infrastructure investments can be unprofitable, and can be obviously playing a key role as provincial GDP Viagra, and yet also be truly transformative and life-changing for the populations that stand to benefit from their construction, especially the poorer rural counties along the route that will gain easier access to their urban neighbors. Using such rationales to deny the economic benefits of the infrastructure to the beneficiaries is cruel. Beyond stimulating provincial GDP growth, the cost of the highway is a humane investment in the people of that region, as well as the likelihood of success for any future poverty alleviation programming that will take place there.

The cost of the highway is a humane investment in the people of that region.

Certainly if the Sichuan government was insolvent overall, it'd be irresponsible and unsustainable to build like this. But if the Sichuan economy is robust enough to finance some “philanthropic” ventures like highways that serve “only a few million” people, why shouldn’t they? Oh, what about local debt, you’re asking? Yes, I know The Economist staff writers have been promising us for years now that this is definitely, certainly, probably, maybe, going to be the year that the local debt bubble pops. And since they’ve now projected 69 of China’s last 0 financial collapses, I can see why that’s concerning.

Jokes aside, Sichuan Development Holdings Company, the local government financing vehicle that built the highway, has spent years building other infrastructure in eastern Sichuan, where the province’s population and economic activities are concentrated. The profitable operation of those highways will subsidize the operation of the Yaxi Expressway and others like it. Fitch Ratings gives SDHC an A-. Sichuan backs SDHC fully, and if Sichuan itself gets itself into trouble, there’s no reason to think Beijing wouldn’t step in decisively with debt-swap support or more assertive measures. My gut reaction to the recently-reinvigorated China local debt defualt risk narrative is: it’ll end up as yet another China collapse nothingburger.

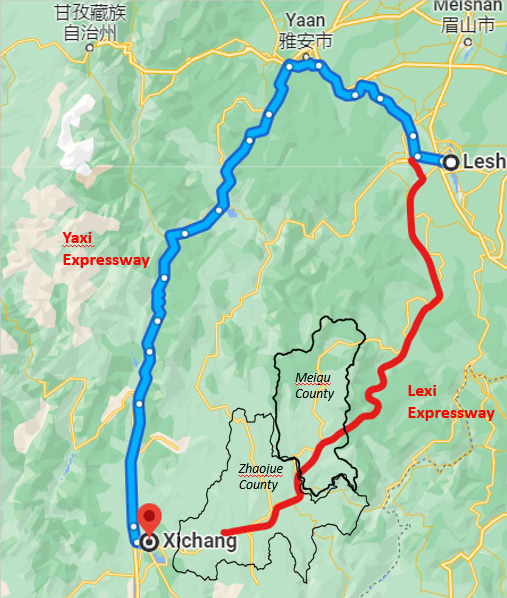

Anyway. Sichuan is building another similar highway right now - the Lexi Expressway - which will stretch from Leshan to Xichang. This one could be even more expensive than the Yaxi Expressway - again, it's all mountains and valleys - in earthquake country, necessitating special construction techniques.

Now…if you’re in Leshan and trying to get to Xichang, it’s actually not really not much of a detour to drive to Ya’an and hop on the already-completed Yaxi Expressway that I discussed already. This is clear from the map I’ve clipped below. This new expressway isn’t about revolutionizing travel between Leshan and Xichang, but more about the places it passes through on the way.

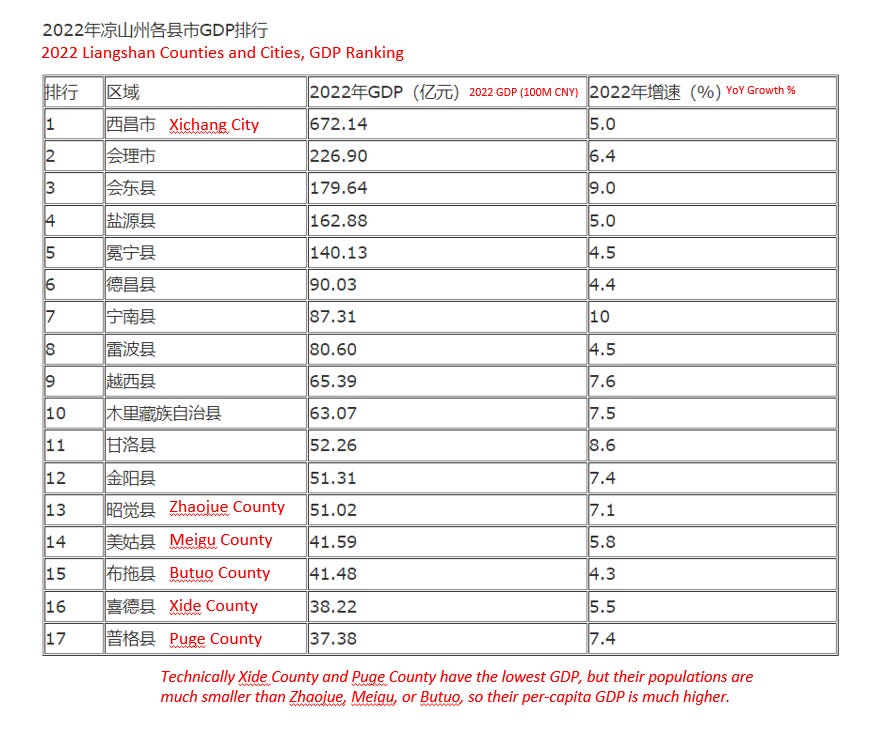

It’s apparent that a major benefit of the new Lexi Expressway will be to bring highway access to the eastern half of the Liangshan Autonomous Prefecture, which was (and still is) infamously one of the most impoverished regions in China. Liangshan’s poorest counties are thus the poorest of the poor anywhere, including places like Meigu County, population 240k, Zhaojue County, population 250k, or Butuo County, population 220k.

While the Lexi Expressway does not appear to pass directly through Butuo, it’s not far either. It crosses right through the other two.

Even after we account for the roughly one-third of their populations working as migrant workers elsewhere, there are still hundreds of thousands of people in these counties, practically and effectively cut off from the rest of the Sichuan economy due to their remote locations. With the low-quality roads there now, it currently takes roughly 4 hours to drive from Meigu County to Xichang, and 5 hours to drive from Meigu to Leshan - these times will be cut in half or more by the new highway.

Of course, it’s worth acknowledging that this region has a LOT working against it beyond just poor roads. In addition to its remoteness, and its total dependence on agriculture, this region was also historically afflicted by high levels of drug abuse and HIV infection. Extensive poverty-alleviation programming here from 2016-2021 saw villages relocated, hospitals constructed, and schools built, but the problems here will take many more years to resolve. When state broadcaster CGTN filmed a documentary on poverty alleviation here in 2020, (focusing on Butuo County) even they were forced to conclude that there’s still a LONG way to go here. It’s a remarkably grim video for state media, and worth a watch:

And, while the region theoretically has natural and cultural resources that could be leveraged for tourism, I still see little evidence of that currently on travel platforms like Ctrip, where there are hardly any attractions for would-be tourists like me to add to my wish-list. If I wanted to visit right now, I’m not even sure how or where I would be able to spend any money in support of the local economy, beyond a few local restaurants and hotels (and the semi-famous cliff village in Meigu).

Naturally, the local government has no money to build-up such attractions, even if they wanted to, and no private developer is going to take a risk on an investment here unless they can reasonably imagine how the tourists are going to arrive. For this region to flourish, it’s going to need tourism, and for tourism to flourish, they need the Lexi Expressway. They deserve that chance.

Is the highway going to magically solve all of Meigu’s problems, and turn it into the next tourist success case, like Tengchong? Of course, that’s impossible to say. There are so many other factors also in play here. But, there is a chance. And on the other hand, without the highway, the likelihood of sustained success in poverty alleviation for this region is close to zero.

Without the highway, the likelihood of sustained success in poverty alleviation for this region is close to zero.

So even if that highway costs an ungodly amount of money to build…and even if it will never pay for itself…and even it only serves a few hundred thousands of people…as long China continues to take poverty alleviation seriously in its planning budgets, (and can sustain the debt) the highway will be built.

I think that’s pretty neat.