The perfect weekend getaway: Escaping Shanghai to cool, green Moganshan

Plus, an ode to coffee, guns, country living, hunting, and sticking it to the man

Last month, I visited Moganshan, a popular scenic mountain region in northern Zhejiang Province, only a few hours from Shanghai. Besides using the time to relax and rejuvenate, I naturally also wanted to learn more about the economic history of the area. I can proudly report that both of my objectives were satisfied, as not only was it a lovely, peaceful weekend getaway, but I also found the perfect local guy to tell me all the juicy stories.

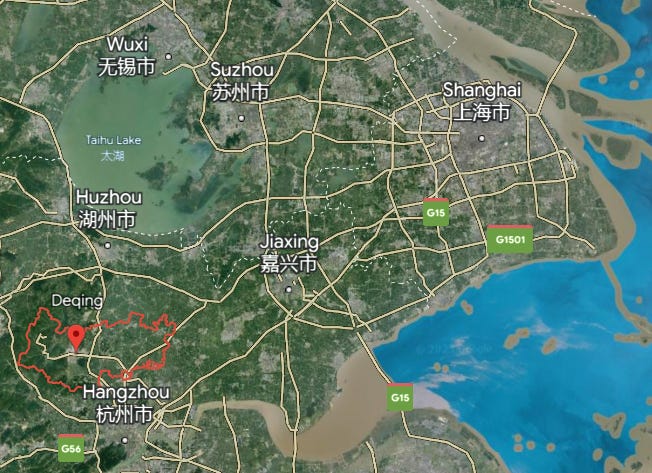

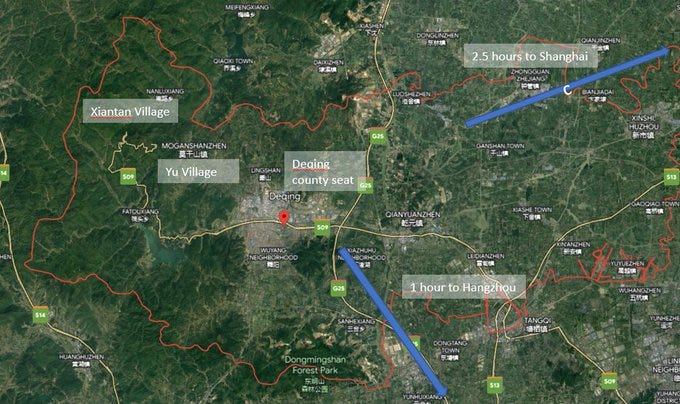

Moganshan is located in Huzhou City’s Deqing County. It’s just over a 2 hours’ drive west of Shanghai, right on the border of where the seemingly endless urban developments start to yield to rolling hills and bamboo forests.

When you visit, you’ll want to go directly to Moganshan Town, which lies to the west of the Deqing County seat. Moganshan Town comprises many villages ringing the mountain proper, with several of them having entrances to the mountain’s scenic area.

Yu Village (庾村) is the lively town seat and most built-up area, lying just outside the east gate to the mountain. However, we wanted peace and quiet, not lively and built-up. That's how we came to choose a guesthouse in sleepy Xiantan Village, to the north of the mountain.

Xiantan Village (仙潭村) is much smaller than Yu Village, with just around 2000 people. Upon arrival, it was clear it would meet our requirements for peaceful and quiet. There was just one road through the village, flanked by larger village manors and grassy fields. Moganshan loomed over the fields to the south, while Mt. Tianquan (Tianquanshan) shaded the village from the north.

Our guesthouse was located in the very back part of the village, halfway up the slope of Mt. Tianquan, facing out to the fields on the valley plain. The owner, and our host, was Mr. Lang. He and his family have run this guesthouse for 20 years, starting out with just their rustic wooden village home in 2003, adding additional units in 2008, and then then finally digging out the side of the mountain to make space for a new three-story guesthouse in 2018. He and his family live on the first floor (along with the reception desk and the breakfast room) while the second and third floors are guestrooms.

Over the time we stayed there, I spent several hours talking with Lang. An energetic 60 years old, he was friendly, chatty, and a wealth of information on local gossip, anecdotes, and commentary on modern Chinese politics. Basically, he was the dream interviewee.

Lang looks like a typical middle-aged Chinese uncle, complete with shoe-polish jet-black hair dye. He smiles easily and his whole face crinkles up when he smiles. When you arrive at the bottom of the hill, he’ll meet you at the parking lot in a golf cart to shuttle guests and their luggage up to the guesthouse on the hillside.

On the way up, I’m surprised to pass a small coffee shop, an unheard-of rarity in the Chinese countryside.

”My new coffee shop!” our host proudly declares. “We just opened it during the Labour Day holiday.”

Lang tells us this coffee shop was built inside of a renovated 120-year old grain storage building. Someone else runs it, but he owns it, and mostly hangs out there during the day.

"I'm addicted to drinking coffee now actually. I like it more than tea" he admits.

Heading further up the hill, we pass by several large dogs, lounging lazily in the sun. "My hunting dogs!" Lang cheerily announces. "Look, you can see their scars".

Sure enough, the dogs' legs and muzzles are covered in old gashes.

"What does that?" I ask. "What do they hunt?"

"Wild pigs!"

“Oh…do those...bite?”

”No, but the males have tusks. When I go hunting, they usually get some new scars”.

"Oh I see. So is it YOU hunting, or is the DOGS hunting?"

"Ah...the dogs are hunting. The dogs chase the pig and I chase the dogs. If the pig is small, they can get it themselves, but if it's big, they drag it down and I'll come with a big knife and..."

"Are wild pigs tasty?"

"Young ones are. Old ones, no. They’re too lean."

”I see…so this is hunting for you.”

"Well, I used to hunt with a rifle. Even after it was made illegal in China, many of us still had rifles here. But later the rules got stricter, and guns become more rare…very few people had them. I know how to use a gun, but sometimes my friend, or my neighbor wanted to borrow mine. If they had an accident...that would be a big problem for me! Maybe jail! So I got rid of it, so they would stop asking."

Lang told me that before he opened his guesthouse, he worked in the bamboo industry, just like everyone else around here. Either you worked on a production team cutting bamboo and hauling it down the mountain, or you made bamboo products - bamboo was the heart of the economy. Lang used to haul bamboo and make street-sweeping brooms to be sold in Shanghai.

"Those days...if you carried bamboo all day, you could make 50 yuan. That's 1500 yuan in a month, for hard work. Young people don't want to do that kind of work now. That's why they leave...there's no jobs for them here. They prefer to go to the city and be a security guard, or work in a factory, rather than do agricultural work."

(50 yuan would be ~6 USD in the year 2000, or ~10 USD in today’s dollars; 1500 yuan would be 179 USD in the year 2000, or around 316 USD today).

"What about tourism?" I ask. "Can young people work here now in the tourism industry...like your son?"

"Yeah, they can come back now if they can find a job in tourism. Take my son...he's got strong arms, he likes the outdoors, but he can't carry bamboo. For that you need strong shoulders and a strong back! He wouldn’t be able to do it."

“I guess you ate a lot differently back then? You probably only had fresh meat once a year, when your family slaughtered the pig for the Spring Festival?”

”No, there was also one other time. Those days, the production team boss would give everyone half a kilogram (one jin) of pork for Mid-Autumn Festival. We always came down from the mountain with fresh meat for the holiday.” Lang’s face lights up as he recalls this long-ago precious boon.

“Besides that, you are correct. We had fresh pork at the New Year, and some cured meat for the rest of the year. But it’s different now. We can eat fresh meat any time we like now. Most families don’t even keep pigs anymore. They smell bad and attract flies…the tourists don’t like it. But I still keep chickens and ducks, up on the mountain.”

Lang's son is 29 and helps him manage the guesthouse. He also has an older daughter who went away to college and works at a company in Hangzhou, the provincial capital. Lang said he and his wife were able to have a second child during the years of the Single Child Policy because his first child was a daughter (a common policy in rural areas). Lang says he’s looking forward to retiring in a few years, leaving the guesthouse for his son, and going traveling. He says the only thing to worry him these days is his son isn't married yet. He cracks a smile. "But I won't push him. He has time."

He admits his days are very relaxed now.

After all, he owns his guesthouse outright, (no bank loans) has few expenses, and can earn the same amount of money from 3 nights renting out a single room in his guesthouse that he used to make from a MONTH of carrying bamboo. So now, he spends his days receiving the occasional guest, drinking coffee, chatting with his neighbors, and just…chilling. And hunting pigs I guess.

Lang proudly told me that back in 2003, he was the 5th villager to open a guesthouse in his village. At the time, it was called Biwu Village 碧坞村 and was much smaller, just around 40 families. It was what China calls a “natural village”, formed by historical grouping patterns. A few years ago, Biwu Village merged with another nearby natural village to become Xiantan Village, which is what China calls an “administrative village”. He still feels a strong sense of identity for Biwu Village, although it doesn’t exist anymore from an administrative standpoint.

"When I first opened my homestay, I wanted people to be happy and feel like they had returned to their hometown, so I called it 快乐老家 (Happy Home). But my daughter came home from college and told me this name is really too tacky. She and her friend thought for a long time and helped me pick a new name, which is the name now, 郎为乔木. I didn't know what it meant, but she told me it had a good meaning, so I said ok!”

(I searched it. It’s part of a line of ancient poetry from the Book of Songs).

I found out that the villagers all opening guesthouses here in the 2000s had nothing to do with Moganshan (which is around 10km away). Actually, Biwu Village has its own natural beauty. One morning, I took a hike in the scenic area behind Biwu Village, up the side of Mt. Tianquan, where I found a lovely series of waterfalls, pools, and rocky cliffs, shaded by bamboo forests, seemingly perfect for a natural attraction. But despite the well-defined paths, traveled by a steady flow of hikers, there was no ticket gate, and no entrance fee.

It turns out, this scenic area had previously been developed back in the 2000s, before being abandoned. At that time, outside investors had arrived in Biwu with the idea of developing the slopes of Mt. Tianquan into the "Biwu Longtan Scenic Area". There were 3 investors, from Taiwan, Fujian, and Zhejiang (Wenzhou). They looked at this place and saw ¥¥, and I don’t blame them.

Now of course, the problem is that the actual land on which their proposed scenic area would lie belonged to villagers from then - Biwu Village. If they were going to develop and access that land, they would need to legally arrange something with the locals - either relocate them, or secure usage rights for their land.

Now remember, this was all back in 2000. At that time it would have been relatively inexpensive to relocate the 40+ households of Biwu Village and gain unrestricted usage rights to their land. Lang laughs about it now:

"It would have been so cheap to move us all to a new location away from the tourist site! Just 100k CNY per household!" (15k USD)

"But they didn't have the capital. Their plan was to develop the site, get it running, then sell it in a few years for a profit. So they rented our land instead. To do this, they calculated...bamboo harvested every 2 years...how much bamboo can grow in 1 mu of land, how many mu does each villager own, etc. They did their calculations and agreed to compensate us in this way.” (1 hectare = 15 mu; 1 acre = ~6 mu).

"Bamboo is harvested in a two-year cycle, so they wanted to pay us every 2 years. But we wanted up-front compensation for a longer guaranteed period, at least 10 years. They paid us for the first 2 years and started selling tickets to the scenic area. But after that, they stopped paying us completely. You, see, they had no capital to pay us more!"

"So we wouldn't allow them to sell tickets anymore. We blocked the entrance and destroyed the ticket booth. The investors said we violated the contract and claimed we were causing them losses. But they violated our rights first, because we didn’t agree to that compensation arrangement.”

Anyway, they sued the village government because that was the counterparty in their agreement, not we villagers. They claimed they spent over 5M CNY developing the area that they had taken as losses. Hah! How could they spend so much?! They didn't even have money to pay us! But they got the mayor to testify for them, so of course they won. The village had to compensate 6M CNY!"

"So this is why we don't trust outsider investors now to develop Biwu Longtan Scenic Area. Actually, some people from the provincial Culture and Tourism Bureau came yesterday and talked to me. They want to have an state-owned investor come in. But we don't trust companies from Beijing or Hangzhou. Maybe a local company..."

"What are your requirements, so that you would feel good about allowing Biwu Longtan development?" I ask.

"Well, of course we must be compensated fairly. I have a successful guesthouse now. It will be more expensive to move me. There are still 20 households in here. You'll need capital!"

"But also I want the new developer to have a plan to show the history of Biwu Longtan. This is a place with history! In the Qing Dynasty, a magistrate from Huzhou came here and left poetry on a cliff. You can barely see it now...most people don't know where it is. But I know."

"Also, there is another piece of history here. We have a local legend that the footpath up the mountain was built by one of you Americans! A foreigner who came here and paid locals to carry stones up the mountain and build a footpath! That's our story anyway. I don't know if it's true".1

"But no development will happen as long as they don't fix the relationship with the local people. The current mayor can't do it...he failed to communicate with us. I think he will be gone next election".

"Would you run for mayor?” I ask. “I think you know a lot about this area…have local connections…and have a lot of ideas"

He laughs.

"Ahh...this...this...this...I won't do this. They asked me to, but I said no. I don't want to be mayor. You always have to go to the county seat, join the Party, do paperwork. So much trouble! And you know what’s worse? If you do a really good job, no one is going to praise you, but if you do a bad job, everyone will be mad at you."

"No, I prefer to be a regular citizen the local government has to care about, has to take consideration of.”2

"The local government has the idea to promote "Big Xiantan" as a model village for development of other villages. But they can't do that while this section of old Biwu Village is undeveloped. When people walk in here through the old town gate, they say it's like a garbage dump! Biwu is not as nice as the rest of Xiantan, because we won’t allow development here”.

"Is the ‘Big Xiantan’ promotion part of Rural Rejuvenation?" I ask.

"Oh yeah, these are all for the Rural Rejuvenation policies. Actually these policies don't have much impact for regular people's lives. It only affects people whose job is politics. It's just some big government plan." Lang launches into a sermon:

"Of course the government needs to have plans. Just like me. I am the head of my family. I need to make plans too, for me, my wife, my daughter, son, son-in-law, granddaughters. They rely on me to choose the family plan. If I don't have a plan, they will not think I'm reliable."

"It's the same for the government. If the government doesn't have a good plan for the people, then they will not be seen as reliable. You know...this is always the way to lead China. The emperor needs to have a good plan for the people, or they will not believe in the emperor."

"Our government has good plans. They are very reasonable and sound good. But they fail in our village because the local officials only care about their own gains, and their promotion. They don't care if it has a bad outcome, as long as they benefit. This is called corruption!"

I jump in: "I saw a study that Chinese people think Beijing is good, the provincial leaders are just ok, the county leaders are bad, and the local leaders are awful. Do you agree with this?

He laughed and shakes a finger at me, saying: “Yes! Yes! This is how we feel in China”. The local government does things without thinking first, without making the right preparation. You know they are now paying for the maintenance fees of Biwu Longtan and Xiantan Scenic Area, although there are no ticket sales? It's not a business operation...it's just an expense item for them."

Despite Lang's complaints about mismanagement, Xiantan (and all of Moganshan) is doing very well versus other rural areas I've visited. From the roads, houses, infrastructure, etc. it's apparent. It has benefited immensely from being in a wealthy province in Hangzhou/Shanghai's back yard. Everywhere, I see signs of “rural luxury”.

In the big picture, Moganshan is far from the most stupendous place I've been in China. Actually, it wouldn't even crack my top 10. It's green and pretty, but that's all. BUT, it's probably the nicest place you can reach driving just 2-3 hours from Shanghai.

And that's HUGE.

That makes Xiantan Village (or any of the Moganshan villages) a useful case study in my opinion. You don't have to have World Class scenery to make a successful tourist area. You just have to be Good Enough, and close enough to a wealthier urban area where people will crave nature and want to get away from the concrete jungle for a weekend.

I think that's the kind of future any savvy, well-managed rural town 1-2 hours from emerging mega-cities like Kunming, Guiyang, Nanchang etc. can look forward to in the coming years, as middle-income urbanites in those cities start craving their own "back yards" that don't have to be World Class, just good enough.

So the new Chinese yuppies will drive their Teslas and their Geelys and their BYDs out to the villages, (where of course they’ll need EV charging) and they’ll eat and drink and comment admiringly on the slow pace of life, and the cheap food, and the blue skies, and the clean water, and idly chit-chat about whether they could imagine owning a home out here (they can’t, unless they have a local residence ID) before heading back to their 30-level concrete tubes in the closest urban jungle.

But not Mr. Lang. The man’s got a plan, and I’ll be shocked if he doesn’t succeed in making it happen. At that point, he’ll be fully retired, perhaps traveling like he said, or perhaps still chasing wild pigs through the bamboo forests of Moganshan, but either way definitely out there living his best life.

He’s earned it.

The Moganshan area has been popular as a summer getaway for foreigners in Shanghai since the late 1800s, so this story is fairly plausible. Anyway, a footpath-commissioning American would surely be an oddly-specific local legend to fabricate.

The exact phrase used was 想做一个政府心里有我的老百姓 - literally “want to be the citizen that the officials keep in their hearts/minds”. I took the implication to be that he likes being respected as a well-connected local with leverage, instead of being the guy on the other side of the table, trying to deal with people like himself.

Another winner! Great stuff, David.

Thanks for sharing these, David- My favorite picture is the single bamboo laid on the ground almost as a bridge. I forget now here in the US how common it is to just teeter and walk along a single stalk like this all over Asia. :)